A new take on British humor

Reuters.com has a section on its website named, “Oddly Enough.” Somehow, I believe that is the source of most of the warm-fuzzy news around the world. Enjoy!

Link to the section.

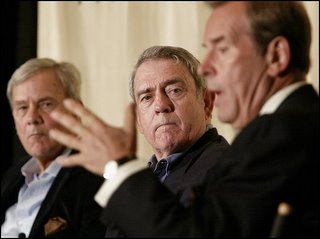

Caption for the photo: CBS anchor Dan Rather at a panel discussion last month with ABC anchor Peter Jennings, right, and NBC anchor Tom Brokaw, who is stepping down next week in favor of Brian Williams. CBS says no decision has been made about a successor to Rather, who will depart in March.

Photo Credit: Gregory Bull – AP(Wednesday, November 24, 2004)

Photo found location

Inside the "Memogate" Affair

By MARY MAPES

[As a veteran producer for 60 Minutes II, the author broke many stories, including the Abu Ghraib torture scandal with Dan Rather. Their next big scoop—the September 2004 exposé on George W. Bush's National Guard service—got her fired, accelerated Rather's retirement, and left CBS reeling. What happened?]

[When CBS's Wednesday-night news program 60 Minutes II was accused of airing falsified documents pertaining to George W. Bush's Vietnam War–era service in the Texas Air National Guard, the resulting scandal effectively shifted the country's focus, at the height of the presidential-campaign season, away from Bush's lackluster military record and toward the shortcomings of the mainstream news media. In an effort to contain the damage, CBS commissioned an independent panel, which published a harshly critical report on January 10, 2005, 10 days before Bush's inauguration for his second term. In response to the report, three network employees were asked to resign, and one—Mary Mapes, the segment's producer, who had worked at CBS News for 15 years—was fired. In these pages, she answers her critics.]

I woke up smiling on September 9, 2004.

My story on George W. Bush's National Guard service had run on 60 Minutes II the night before and I felt it had been a solid piece. We had worked under tremendous pressure because of the short time frame and the explosive content, but we'd made our deadline, and, most important, we'd made news.

Dan Rather and I had aired the first-ever interview with former Texas speaker of the house and lieutenant governor Ben Barnes on his role in helping Bush get into the Texas Air National Guard. Getting Barnes to say yes had taken five years, and I thought his interview was a home run. Finally, there were on-the-record, honest, straight-ahead answers from a man who intimately knew the ins and outs of the way Texas politics and privilege worked in the state National Guard units during the Vietnam War.

Our story also presented never-before-seen documents purportedly written in 1972 and 1973 by Bush's then commander, Lieutenant Colonel Jerry B. Killian, who died in 1984. These documents appeared to show that Killian had not approved of Bush's departure from the Guard in 1972 to work on a U.S. Senate campaign for Republican Winton Blount in Alabama. They seemed to indicate that Killian had ordered Bush to take a physical that was never completed and that Killian had been pressured from higher up to write better reports on Bush than were merited by the future president's performance. The Killian memos, as they came to be called, challenged the version of George W. Bush's Guard career that the White House had presented.

I had spent weeks trying to get these pieces of paper and every waking hour since I had received them vetting each document for factual errors or red flags. I compared the new memos with Bush's official records, which I had been collecting since 1999, when it first became apparent that he would be running for president. They meshed in ways large and small.

Furthermore, the essential truth of the story contained in the memos had been corroborated by Killian's commander Major General Bobby Hodges in a phone conversation two days before the story aired. He said the memos reflected what he remembered about how Killian had handled Bush's departure from the Guard.

We had a senior document analyst named Marcel Matley fly to New York to look at all the documents we had, the official records that had been previously released by the White House as well as the "new" ones. After examining them for hours, blowing up signatures and comparing curves, strokes, and dots, he said he saw nothing to indicate that the memos had been doctored or had not been produced in the early 1970s. A second analyst, James Pierce, agreed.

I felt that I was in the clear, that I had done my job, and that the story met the high standards demanded by 60 Minutes II.

When I got to work, I ran into other producers and correspondents and collected hugs and kisses and congratulations. There were jokes about what we would do as a follow-up. Dan and I had broken the Abu Ghraib prison-abuse story in late April, a few days before Seymour Hersh of The New Yorker came out with his story on the subject. All of us at 60 Minutes II felt like we were on a roll.

Things began to change at about 11 a.m., when I started hearing rumbles from some producers at CBS News that a handful of far-right Web sites were saying the documents had been forged.

I was incredulous. That couldn't be possible. When we'd shown the president's people the memos, the White House hadn't attempted to deny the truth of the documents. In fact, the president's communications director, Dan Bartlett, had claimed that the documents supported their version of events: that then Lieutenant Bush had asked for permission to leave the unit.

Within a few minutes, I was visiting Web sites I had never heard of: Free Republic, Little Green Footballs, Power Line. They were hard-core, politically angry, hyperconservative sites loaded with vitriol about Dan Rather and CBS. People posted their questionable recollections that electric typewriters in the 1970s did not do "superscripts," the small "th" or "st" suffixes following a number and lifted higher than the other letters. This was important because, in the Killian memos, "111th" was sometimes typed with a superscript. Other bloggers claimed there was no proportional spacing on old typewriters—using different widths for different characters—even though some of the old official documents had proportional spacing. The claims snowballed.

I remember staring, disheartened and angry, at one posting. "60 Minutes is going down," the writer crowed.

I phoned Matley, who said he had seen some of the comments and dismissed them out of hand. He disdained the anonymity of the postings, saying that any real analysts would use their names and credentials. And he pointed out that, in the process of downloading, scanning, faxing, and photocopying, some computers, copiers, and faxes changed spacing and altered the appearance and detail of fonts. He thought that a basic misunderstanding of how documents changed through electronic transmittal was behind the unfounded certainty and ferocity of the attack on the documents.

I thought Matley's belief that a technical misunderstanding was all that was behind the ferocious attack was too good to be true. He knew a great deal about documents and signatures. But I knew attack politics.

I remember looking at the Drudge Report at about three p.m. and seeing that the lead was a huge picture of Dan with a headline that read something like SHAKEN AND STUNNED, RATHER HIDING IN OFFICE.

The phone rang and it was Dan. "Mary, someone has just handed me something from the Drudge Report saying that I am all shook up and hiding in my office. I just want you to know that's not true. I'm not worried and I'm not even in my goddamned office."

I knew I could count on Dan. He told me that he had confidence in the story and that he was lucky to work with me. He signed off by saying something that had become a shorthand for us over the years: "F-E-A." That was code for "F— 'Em All," a sentiment that needs to be expressed from time to time in any newsroom. Dan was too much of a gentleman to say the real thing—at least most of the time. [Rather could not be reached for comment on this story.]

The day continued to deteriorate. I got a stream of phone calls from Betsy West, a CBS News senior vice president, and Josh Howard, the new executive producer of 60 Minutes II. Their calls all began with the same ominous words: "Mary, we've gotten a call from [fill in the blank]." It could be The Washington Post, The New York Times, the New York Post, the Los Angeles Times. It felt as though the whole world were reading the blogs and repeating their talking points without questioning them.

We put our heads down and aired a strong and reasoned defense on the CBS Evening News the next night. Dan ended the report by asking that the president answer the long-standing questions about his National Guard service. But no one listened. Everyone in the media wanted to cover CBS, not the National Guard story.

On the night of Friday, September 10, we found we had a new problem. General Bobby Hodges, the man who had corroborated the content of the documents before we aired our story, called to say that he had seen all the coverage and he, too, thought the documents were forgeries.

With horror, I realized I had no recording of his earlier corroboration. I felt sick. I read him the notes I had taken during our previous conversation, on Labor Day, September 6. He admitted he had indeed said all those things but insisted that now he didn't think the memos were real. [Hodges later told the CBS panel he did not confirm the contents of the memos.]

Late that night, CBS News president Andrew Heyward showed up at the 60 Minutes building, something that I didn't see happen very often. I joined him, along with Josh Howard, in Betsy West's office. Andrew asked how many document analysts we could summon for a news conference on Monday. He visualized a sea of analysts who would literally "stand behind the documents." I reminded him that they were photocopies, not original documents. There was no ink or paper to test. No reputable analyst would give 100 percent assurance of authenticity or of fabrication, a point I had made clear from the beginning.

"But they have people who are doing that, Mary," Andrew said, "and it's killing us. If the blogs are using people that are lousy analysts to make their case, then let's get some lousy analysts of our own." I couldn't believe it. That's not what reporting is supposed to be.

[In an e-mailed response from CBS News, Heyward denied asking how many analysts could be summoned for a news conference or suggesting that CBS find "lousy analysts." CBS News also claimed that Mapes "insisted that the story and the documents were 100% reliable and that there was absolutely no problem."]

I had a conference call at nine the next morning with our public-relations people and Josh, Betsy, and Andrew. We agreed we were in deep trouble and tried to brainstorm ways to begin digging out of the mess. Near the end of the call, Andrew yelled into the phone that "if someone fucked this up, they'll be phoning in from Alcatraz." Nothing like a vote of no confidence to help build your stamina for a long campaign.

[According to CBS News, "Mr. Heyward never raised his voice. He did say, in a normal tone of voice, 'If we're wrong about this, we'll be apologizing from Alcatraz.'"]

There was a great deal I didn't know back in September 2004.

I didn't know that the attack on CBS News and the story we aired was just another part of the Bush supporters' aggressive pattern of sliming anyone and everyone who raised questions about the president.

In the months before the 2004 election, the White House certainly didn't want the country talking about the choices young Lieutenant Bush made during the Vietnam War. I thought it was a good time to talk about it. But then, I didn't see our story as an attack on the president. We were simply reporting what we had found. But to the defenders of George W. Bush, our story was a declaration of war.

I didn't know that the attack on our story was going to be as effective as a brilliantly run national political campaign, because that is what it was: a political campaign. I didn't know that we were being bombarded by an army of Bush backers with different divisions, different weapons, and different techniques, but always the same agenda: Kill the messenger.

I didn't know that, when it came to CBS News, Viacom co-president Les Moonves was telling friends half-jokingly that he wanted to "bomb the whole building," according to The New York Times Magazine. It turned out that Moonves wanted CBS News to be more entertaining, more upbeat, more fun.

Caught between political and corporate interests, I ended up fired—cast out of the news clubhouse, tagged by many as a person whose politics drove her journalism. Journalists should do their best to set aside personal views when doing their jobs, but I can no longer stay silent. I must answer the bloggers, the babblers and blabbers, and the true believers who have called me everything from a "feminazi" to an "elitist" liberal to an "idiot."

If I was an idiot, it was for believing in a free press that is able to do its job without fear or favor.

If I am an elitist liberal, I have to blame it on my privileged background. I grew up in an elitist-liberal hothouse, a tiny farm in Washington State, where for generations my family worked from daylight to darkness, feeding cattle, raising crops, and watching the skies obsessively, hoping for good weather. Like most elitist liberals, I learned to drive a tractor, rake hay, and harrow pastures long before I sat behind the wheel of a car.

When I stepped in shit—literally, on some days—nobody bailed me out. In my family, we learned quickly we had to clean up after ourselves. I did not have wealthy parents or influential family friends to help me. I still know manure when I see it. And I know the people who attacked my story are more gifted at working with fertilizer than facts.

I made my first round of phone calls on George W. Bush's military service in the summer of 1999. By then, I was working full-time at 60 Minutes II, the newly launched Wednesday-night offshoot of the long-running Sunday program. I had lived in Dallas since 1989 and had covered Bush for the CBS Evening News, so I was familiar with the simmering controversy over his National Guard service.

President Bush entered the Texas Air National Guard in May 1968, the bloodiest month for American soldiers in Vietnam. He had just finished college, and graduate-school deferments were no longer available. Because his father was a Texas congressman, Bush was able to meet the Texas Guard officials who ran a unit based in Houston, part of his father's district, and tell them in person that he wanted to join the Guard and be a fighter pilot like his dad. Although Bush scored only a 25 out of 100 on his pilot aptitude test, he was awarded a coveted training spot.

The young airman trained at Moody Air Force Base, in Georgia, where he may be best remembered for the time in 1969 when then President Nixon sent a government plane to pick him up for a date in Washington with First Daughter Tricia.

After completing his initial instruction, Lieutenant Bush signed papers promising to fly for five more years, until late 1974. He was then sent to Ellington Air Force Base, near Houston, to serve with the 111th Fighter Interceptor Squadron. There, Bush trained on and flew the F-102, a fighter jet not much in use in Vietnam. But then he'd already signed papers saying he didn't want to go overseas.

For a little more than two years, he continued to fly the F-102. His assessments appear to have been good. Then, in April 1972, according to Bush's flight records, the future president climbed out of the cockpit and walked away.

George W. Bush says that during his absence from Houston he was working on a Senate campaign in Alabama and pulling weekend drills at a nearby Guard base. Scant evidence has been found to support his claim of serving in Alabama, however, and he didn't return to his unit in Houston until late May 1973, six months after his candidate lost the election.

That fall, Bush was released to go back East and attend Harvard Business School. After breaking a promise to join a reserve unit in that area, he sought and won a final separation from duty.

I thought this was a significant story, an insight into who George W. Bush was and what kind of life he had led. It became even more important when Bush made National Guard troops such a central part of the fighting force in Iraq. This was just the kind of active duty the president had managed to avoid.

By midsummer of 2004, as Bush was running for re-election, the Texas gossip grapevine was beginning to reverberate with word that someone had new documents involving his Guard service. Eventually, the rumors led me to Bill Burkett, a former cattle rancher who lived in the wilds of West Texas. In February 2004, Burkett had gone public with a tale about witnessing what he called a "cleansing" of Bush documents at Texas National Guard headquarters in Austin in 1997, while Bush was governor. One of the people Burkett relied on to back him up had denied all knowledge, leaving Burkett to twist in the wind. He was generally viewed by the press as an anti-Bush zealot. That is how I regarded him, too.

Burkett had left the Guard in the late 1990s, in what appeared to be one of the organization's seemingly constant personnel purges. I knew Burkett didn't like Bush. As governor, Bush didn't do what Burkett thought was needed to clean up the Guard's endemic corruption. And I knew Burkett was bitter over what he felt was unfair treatment with regard to medical problems he said he developed while stationed in Panama for the Guard.

But bitterness, medical problems, political differences, and an angry departure from a workplace don't disqualify someone from serving as a source. In fact, those are often defining elements for a whistle-blower. I decided to keep talking to Burkett.

Finally, late in August, Burkett agreed to get together with an experienced Austin-based researcher named Mike Smith and myself. On Thursday, September 2, we met Burkett and his wife, Nicki, at a family-owned pizza place in Clyde, Texas, a small town not far from their home. Inside, Bill Burkett reached into a blue folder and pulled out a white sheet of paper with a few paragraphs typed on it. I saw the heading "111th Fighter Interceptor Squadron" and the date "01 August 1972." I knew that was the date referred to in the official record as the day Bush's commander suspended the young first lieutenant's flight status.

The memo said that Bush was being suspended not just for "failure to meet annual physical examination (flight) as ordered," but also for "failure to perform to USAF/TexANG standards." That was new. And it was big.

The document said that Bush "has made no attempt to meet his training certification or flight physical" and that he "expresses desire to transfer out of state including assignment to non-flying billets." The statement about Bush making "no attempt" to meet his certification or to get his physical sounded bad. It sounded as if, instead of arranging for an orderly transfer to Alabama, he'd ducked his duty.

I looked up and told Burkett my greatest fear was that this was a political dirty trick, something one side or the other might pull to hurt either the president or the newspeople who ran with the document. Burkett looked hurt and genuinely shocked. "I can't believe someone would hate me that much," he said. Then Burkett handed over another document. This one also contained information that was damning to the president. I didn't grill Burkett on where he had gotten them. I knew him well enough to worry that, if I gave him time to take the documents back, he was fully capable of doing just that.

The first thing we found out from the document analysts was that without originals there was no way we could ever date the documents physically. The memos we had were copies or, more likely, copies of copies. But we had no reason to think that this factor, in itself, should bring our story to a screeching halt. Most news reports involving documents—whether the Pentagon Papers or garden-variety court records—are based on copies of documents, not the originals. What was most important to us was finding information that would validate or negate the documents and what they contained. Scientific proof isn't the journalistic standard in such a case. Solid, compelling evidence is.

Analyzing the content of the memos, comparing each detail of information with the official records, getting corroboration from anyone else associated with Bush's unit—those were the things that could give us a sense of whether these memos were the real thing. This became even more urgent when Burkett produced four additional memos, including one in which Killian complained of pressure to "sugar coat" Bush's annual review.

I did not find the kinds of telltale flaws that give away forgeries. The addresses were right, the dates were right, the references to the 1972 Air Force Manual cited the right page and the right paragraph. Even Bush's service number, which had been blacked out on many officially released documents, was correct. When Bush's former commander confirmed to me that Killian had been miffed at Bush's departure for Alabama, that Killian had complained about it, and that the sentiments in the memos were familiar to him, I felt we were home free. The clear preponderance of evidence supported the idea that these memos were real. We had to go with the report.

I had envisioned running the story in mid- to late September, but Josh Howard explained that there were some stumbling blocks. Our time slot on September 15 would be taken over by a Billy Graham crusade in about a third of the country, Josh said, and 60 Minutes II would be pre-empted on September 22 because of an hour-long Dr. Phil special. So our choices were really the 8th—just six days after our meeting with the Burketts—or the 29th.

We already knew that many news organizations were chasing the president's National Guard documents. In sizing up our Bush-Guard story—Josh's very first as executive producer on 60 Minutes II—Josh wanted us to push as hard as we could and get it on the air as soon as possible.

We worked like demons, and at about two in the afternoon on September 8 we had our first screening of the piece, which was set to run that night. It was a few minutes too long, and when the lights went up, Josh made it clear he wanted to leave out the section quoting from the new and old documents and showing how they folded together. He thought it was too confusing, too inside-baseball.

Josh also wanted to remove a section from the script where we reported that General Hodges, Colonel Killian's direct commander, had corroborated the memos' contents. We were now excluding altogether two of our strongest reasons for believing that the memos were real. Two of the three sturdy legs supporting our story were knocked aside in haste. [Josh Howard told the CBS panel that it was Mapes who requested taking out the reference to General Hodges.]

The piece we were left with made it look as though our trust in the new memos rested entirely on the word of Marcel Matley, who had examined all six memos, and James Pierce, who had seen the original two. Two other analysts had seen the first two memos as well: Linda James told me she needed to see originals in order to determine their authenticity, and Emily Will raised questions about the superscript "th." [Will says she called CBS before the segment aired, warning that the documents were problematic.]

I was uncomfortable with the script, and in retrospect I should have done something I'd never done at CBS before. I should have said, "No." Instead, I went back to work.

Dan came in and quickly recorded changes in narration. We all watched the story one more time, and then Josh said he had to take it. I was later told that the tape of the story was shown to Andrew Heyward. By then I had collapsed on a colleague's couch.

The story aired at eight, and on the broadcast it looked solid. I began to beat myself up for being so worried. Friends and colleagues called to congratulate me. Dan was pleased. By the barest of margins, it seemed we had pulled it off.

I didn't know the exact chronology of our demise until long after the shouting and the shrieking had died down.

Just before midnight eastern time, a few hours after the broadcast, an anonymous writer calling himself Buckhead posted a long analysis of our memos based on what he claimed were facts about typography. His screed appeared first on the conservative Free Republic Web site. Whoever he was, Buckhead wrote like he really knew his way around the history of type, typewriters, and computer printing:

"Every single one of these memos to file is in a proportionally spaced font, probably Palatino or Times New Roman. In 1972 people used typewriters for this sort of thing, and typewriters used monospaced fonts. The use of proportionally spaced fonts did not come into common use for office memos until the introduction of laser printers, word processing software, and personal computers.… I am saying these documents are forgeries, run through a copier for 15 generations to make them look old."

Buckhead's conclusions and accusations were immediately echoed on a bouquet of other far-right Web sites—particularly Power Line and Little Green Footballs—places that most of the mainstream media had never heard of but would learn about in the hours, days, and weeks ahead. Their claims, unsubstantiated as they were, went virtually unchallenged by mainstream journalists, who didn't know a damned thing about typeface, kerning, or proportional spacing, either, but tried hard to appear as if they did. Skepticism, a supposed hallmark of journalism, was largely forgotten.

As it turns out, Buckhead is no stranger to conservative causes. The Los Angeles Times revealed that his name is Harry W. MacDougald, and he is an Atlanta lawyer with years of experience working on right-wing issues. In his day job as a litigator—where MacDougald presumably uses his real name—he is affiliated with two conservative legal groups, the Southeastern Legal Foundation and the Federalist Society.

MacDougald was also a key player in drafting the petition that eventually won a five-year suspension of Bill Clinton's Arkansas law license after Clinton's misleading testimony in the Paula Jones sexual-harassment case.

Within CBS, we were approaching full panic. Part of the problem was that we suddenly found ourselves in a war and the network didn't know how to fight wars. It didn't have a war room. It didn't have a war mentality. The CBS press office was used to creating timeless blurbs such as: "Hear from Jennifer, the morning after she lost the Tribal Council tiebreaker."

One CBS P.R. man was brought in specifically to help, a confidant of Les Moonves's named Gil Schwartz. On September 10, two days after our story ran, Gil sent me an e-mail. "If we can destroy the 'th' issue, we're way ahead," it said.

He meant that he wanted to address the subject of the superscript. Critics said that it didn't exist on typewriters at the time the memos were supposed to have been written. But it did exist. We would report this on the CBS Evening News that night.

A number of us had stayed up half the night on September 9, going through Bush documents released by the government until we found contemporaneous examples of a small superscript "th." One example that we found in Bush's official record appeared to have been typed as early as 1968, and we planned to put it on the air and release it online. Although the "th" in the official document was not identical to those in the Killian memos, it demonstrated that typewriters of the period were equipped to create superscripts.

I was terribly frustrated, and I barked back at Gil in an e-mail: "For the 1000th time, the 'th' issue is gone. We have examples from the 'official' White House docs. We're set." Gil decided to lecture his dim-witted colleague:

"The problem, Mary, is one of perception. As far as the press is concerned, the 'th' issue is NOT gone. It's very much alive, and they have people crawling all over it. If we wait to address the issue until tonight's news, we will DIE in the press tomorrow. Die. As in … dead. You tell me. How do I get the message out RIGHT NOW, as in RIGHT THIS VERY MINUTE, that the 'th' thing is no longer an issue?"

What could I do? I was a journalist. I didn't have a clue how to launch or win a P.R. war.

On September 15, we aired an interview with Marian Carr Knox, an 86-year-old former secretary to Jerry Killian. She said she had seen how then Lieutenant Bush got favorable treatment and how he had avoided taking his physical, upsetting Colonel Killian and creating resentment among the other pilots. The only problem was that she said she also thought the memos were fakes because she hadn't typed them.

The next morning, Andrew called me and tersely asked me to set up a conference call with Bill Burkett for later that day. I arranged the phone call, and at the appointed time Betsy, Dan, and I were shown into Andrew's office.

A couple of days after I got the Killian documents from Burkett, I had begun hounding him about how he had gotten them. Finally, Burkett broke down and grumbled that he had gotten the papers from George Conn, a former National Guard colleague of his. Burkett said Conn would never confirm his story, but I began trying to reach Conn anyway.

In the call with Andrew, however, Burkett said he had created the story about Conn to get me to back off. Burkett said he had promised his real source to keep the truth a secret.

Now Burkett poured it out on the speakerphone to our shell-shocked group. He said he had received a phone call in late February of 2004 from a woman named Lucy Ramirez who wanted to speak with him. Burkett said he was told to call her back at a Houston Holiday Inn a few days later. Burkett said Ramirez told him she was supposed to deliver a package of documents to him.

Burkett told us that Ramirez made him promise that he would handle the package in a very specific way. He agreed to copy the documents inside, then burn the papers themselves, which were also photocopies, together with the envelope. Burkett said that he agreed to this, assuming that Lucy or whoever she was wanted to destroy any DNA evidence.

Burkett said that Ramirez asked him if and when he would be in Houston, and he told her he would be at the Houston Livestock Show and Rodeo within a couple of weeks, working a breed booth. Burkett said that on his first day working the booth he was handed the papers by a "dark-complected" man. An acquaintance of Burkett's confirmed to USA Today that he was at a Houston livestock show in early March and that, as Burkett told CBS, he asked her to hold papers for him in a box she had at the show.

While Burkett's tale unwound in Andrew's office, I looked around the room and saw that Betsy and Andrew were openmouthed, blinking, blinded by their sudden exposure to the weirdness that is and always will be Texas. Dan, having been born and raised in Texas, took the colorful story more in stride.

Before hanging up with Bill Burkett, Andrew asked if he would be willing to go public and do an interview laying out his whole story. Burkett agreed. We settled on doing the shoot in Dallas that Saturday, September 18. I thought it was possible that his stepping forward would actually help the story when viewers saw that Burkett wasn't a slick political operative or a fire-breathing three-headed ideologue.

Betsy and Dan were the last to arrive at the Dallas hotel, and they looked tired. I took Betsy to the Burketts' room first. The Burketts told Betsy that this story could end up costing them everything. Nicki stood in her shapeless cotton shift and told Betsy, "Here I stand dressed like a little peasant, hoping and praying that you're going to treat us fairly."

The room was quiet by the time Dan came in to greet the Burketts. Dan told Burkett that he was going to ask him why he had misled us about where the memos had come from. Burkett said he expected that and he very much wanted to set matters straight.

Dan told the Burketts that he had to go get his "war paint" on, and I went with him across the hall to his room. Once inside, he said, "You know, Mary, I think he is a truth teller." I thought so, too. But Bill Burkett's version of the truth could get pretty convoluted. It could be hard to see clearly. It could be self-serving. However, I didn't think for a moment that Burkett was capable of doing anything like forging documents, faking old memos, or giving anyone in the media something that he knew had been faked.

As we talked, Dan's door burst open and Betsy flew in, declaring, "Something very odd is happening in there." She nodded toward the Burketts' room, across the hall. She said that when she opened the door to their room, she saw that they were "on the ground, on their knees, at the side of the bed," mumbling. "For God's sake, Betsy, this is Texas," I told her. "They're praying."

Finally, Burkett and Dan took their seats under the great arc of lights at the front of the big room and the interview began.

Betsy stayed focused on trying to get the most self-incriminating comments possible out of Burkett. In her defense, I strongly believe that's what she had been ordered to do to protect the company and separate CBS News from Burkett as much as possible. Again and again, Betsy handed me notes that I would read and take to Dan during a break. The notes hit over and over on one thing: Ask him why he lied about where the memos came from.

Burkett, after putting the best face he could on his imperfections, said flat out that he had not told the entire truth in order to protect others. Betsy wanted more. I could see Nicki pacing off to the side and growing angrier and angrier. Dan was unhappy, and eventually he cut off the questioning.

We went back to our rooms. No one felt good. Dan packed up quickly and headed for the airport to catch a plane to Austin so he could visit his daughter. Betsy, Mike Smith, and I were sitting in Dan's abandoned room when there was a light knock on the door.

It was Nicki, a small figure in that plain dress, her eyes glistening and her lips pursed. Betsy made the mistake of asking, "Why is Bill so upset?"

Nicki erupted. "You asked Bill the same question over and over and over again trying to trip him up and catch him in a lie, but you couldn't because he didn't lie. You may think I am just some hick that doesn't know any better. But I am smart enough to know what you just did. You put a knife in Bill's back. And I'm damned sure smart enough to know that." Nicki turned with a whoosh and marched out, slamming the door behind her.

On Sunday, I had barely made it to baggage claim at New York's LaGuardia Airport when my cell phone rang. It was Dan calling from Austin.

"Mary," he said, "Andrew has decided to make an announcement tomorrow, apologizing for the story and saying that we cannot authenticate the documents." He let that sink in, then went on: "Furthermore, he tells me that he is going to appoint an independent panel to investigate the way the story was put together. Andrew thinks, he is not sure, but he thinks the panel is going to be headed up by Dick Thornburgh, the former attorney general."

I was reeling. I leaned against a wall and listened, my heart in my throat. "Now, Mary, this is very bad, and this is going to be very hard. And I am calling to tell you this, not just to give you a heads-up that this is what's coming, but because I want you to get yourself a lawyer as fast as you can." He took a deep breath. "You need to start protecting yourself. We all do."

I told Dan that I appreciated his tip. I told him good-bye. And I went to the ladies' room at LaGuardia and cried my eyes out. Jesus Christ, I was finished.

CBS News soon issued a statement that it could no longer stand by the Bush-Guard story, and announced that it would select an independent panel to investigate what had gone wrong on the story. Burkett's confession as to misleading us about where he had gotten the documents gave Andrew Heyward and corporate CBS the cover they needed. They were looking for a way out, and Burkett's changing his story must have seemed heaven-sent. I don't know what would have happened if Burkett had stuck to his original story.

It was late October and New York's weather had become chilly. My lawyer, Dick Hibey, law associate Dan Lewis, and I turned up our collars as we walked through the wind toward Black Rock, CBS's famously imposing corporate headquarters. Lewis struggled to pull along his spindly metal cart stacked high with boxes and black notebooks—copies of my notes on phone calls and conversations with sources, my e-mails, some of my phone records, my journalistic secrets. They all had been requested by the panel, and my bosses told me I had to comply. The network had already downloaded all my e-mails from the past who-knew-how-many months and given them to the panel.

The panel members were lawyers from the massive law firm of Kirkpatrick & Lockhart Nicholson Graham, a Washington powerhouse—with the exception of former Associated Press C.E.O. Louis D. Boccardi, who had participated in the New York Times investigation of the Jayson Blair case.

Dick Thornburgh, the Republican former governor of Pennsylvania and attorney general under President George H. W. Bush, is also known to television viewers as one of the first American victims of comedian Sacha Baron Cohen's obtuse alter ego Ali G, who asked Thornburgh, "What is legal?," "What is illegal?," and "What is Barely Legal ?" Thornburgh, who apparently did not catch the joke in this line of questioning, was asked by CBS News to assess the investigative work of the 60 Minutes II team.

I knew that the panel had been asking whether I had been obsessed by the story or by President Bush himself. I knew they wondered if I was a liberal, a Bush-basher, or maybe a hothead. At least one person had been asked whether I had tried to physically intimidate people. Good Lord. I didn't know whether to laugh or cry at such a twisted line of inquiry.

I met the panel in a large boardroom. They were very mannerly and very corporate. Dick Thornburgh was quite tall. Lou Boccardi, quite short. In fact, he was tiny. I wondered if he was afraid I might turn over the table and put up my dukes.

The panel wanted to know if I had questioned Burkett that day in Clyde, Texas, on the "provenance" of the documents. I hadn't done that. I just wanted to get the papers and get out of there and start working to see if the documents were real. It seemed to me that the panel felt I should have single-handedly put Burkett under oath and then grilled him on the details of his story.

I had to laugh to myself at some of the panel's rigid, legalistic ideas of how reporting should work. With these guys running the newsroom, the details of Watergate would have stayed with Deep Throat in the parking garage. Based on their questioning, I'm convinced that Dick Thornburgh would have found Mark Felt an inadequate source, clearly a person with an agenda or political and personal motivations, something he and the panel thought was inappropriate.

On the second day of hearings, the panel began picking apart countless e-mails that had been dashed off months earlier without a second thought. At one point, Thornburgh motioned that he had something to say. "You'll have to pardon my language here," he droned.

"You mean my language, right?," I answered, trying to make light of whatever was to come.

"Yes, it is your language," he said flatly. Oh, shit. What had I said?

"You've written here, 'I am so sick of all of this horseshit.' What did you mean by that?" he asked. I looked at the offending e-mail and saw that it had been sent to Betsy West back in September in the context of complaining about the bloggers and their attacks. I told him I had been talking about bloggers and the bad information they were putting out.

"No, that's not what I mean," he went on. "Why did you have to use that word? What did you mean by 'horseshit'?"

What could I say? That "bullshit" is overused and "chickenshit" has an entirely different connotation? I was dumbfounded and finally stammered my way to a conclusion, confessing that I had used the word "horseshit" because I had a horse as a kid and it seemed to suit the situation.

Thornburgh leaned back, looked triumphantly around the table, then finished with "I'm O.K. Who's next?"

I thought back to how Thornburgh had been described to me as an "empty suit," the perfect person for politics, a blank slate ready to carry out whatever orders he got from headquarters. Now I knew differently. He wasn't an empty suit at all. He was completely full of it. Horseshit, that is.

I returned for another round of questioning on December 8. This time, we convened in Washington, where the lawyers took turns trying to ask questions that I couldn't answer. Time and again, they swung and missed.

I knew they had asked everyone else about my politics, and I couldn't believe that they wouldn't hit me up for what kind of card I carried, too. When it appeared we were wrapping for the day and the topic still hadn't come up, I finally said something. "Aren't you guys going to ask about my politics?"

I could see Dick Hibey glaring at me as though I had gone mad. But Lou Boccardi jumped at the chance. "Well," he said, "wouldn't you say it's true that most of the people that you work with think you are a liberal?"

"You mean, are you asking me, 'Am I now or have I ever been a liberal?,'" I said, a joking reference to the 1950s U.S. Senate hearings where Senator Joseph McCarthy grilled people as to whether they had ever been members of the Communist Party.

Lou pressed on. "Wouldn't you describe yourself as a liberal?"

I began talking about my beliefs, about how life is complicated and how labels are not one-size-fits-all. I told them I didn't support the death penalty. I told them that, as an adoptive mother, I had complicated feelings about abortion. My lawyer was giving me the "Shut up, you idiot" look.

Finally, I did shut up, but only after the panel had made it clear, or so it seemed to me, that they thought I was a liberal and that, moreover, they felt they had strong proof I was a liberal.

I couldn't help but reflect sadly on what had become of CBS News. The once proud network whose anchorman had bravely called out Joseph McCarthy and denounced his witch hunts in Washington now had returned its agents to the capital with a different agenda. This time, the network hired high-powered lawyers to do some hunting of their own among the news division's journalists. Suspected "liberals" had become the new Communists. People who'd had long and successful careers at CBS, whose work had never before been questioned or criticized, were suddenly grilled as though they were strangers under investigation for committing unspeakable crimes. The network had eagerly handed over to the panel my notes, phone records, and e-mails to be used against me. What in the world would Edward R. Murrow think of his network now?

This time, however, politics was only part of the equation. Money was at the center of this inquisition. I am convinced that CBS and Viacom did not want an angry administration making vindictive decisions that would cost them a single dollar. Viacom has spent millions lobbying Washington, asking for leniency on issues ranging from decency standards to the limits on ownership of media outlets. Nothing that could impact the company financially was left to chance.

So the executives decided to stage this upside-down, inside-out re-enactment of the famous face-off between Murrow and McCarthy. At this new CBS, the journalists were the bad guys. The corporate fat cats would cloak themselves as seekers of truth. And the American public and its right to be informed? Well, who gave a damn about that? It never even came up.

All of this didn't just break my heart. It was breaking CBS.

Finally, on the morning of January 10, after weeks and weeks of excruciating delay, I got an early call from a friend inside CBS in New York saying the report was coming out that day. This was it.

By nine a.m., my wait was over. The phone rang. It was Andrew Heyward. He spoke quickly and without emotion. "Mary," he said, "the report is out and it's very bad. I'm going to put [CBS executive] Jonathan Anschell on the line. Jon, get on." I knew instantly what would happen next. CBS policy requires a witness to any firing, even on the phone.

"Mary? Jonathan? Can you hear me?" Andrew's voice had gotten more hollow, more distant. I was going to be fired on a freaking speakerphone. Nice touch.

"Mary, as I said, the report is out. It's very bad. You're being terminated."

Dick Hibey called and told me he was sorry. He also gave me some information that Andrew hadn't bothered sharing. Josh Howard, Betsy West, and Mary Murphy, the senior broadcast producer under Josh, were being asked to resign. I had been fired. I was the clear villain. They were being asked to step down. They must have been sort of subvillains. Frankly, I was shocked at this.

Ironically, the panel did not find conclusive evidence that the documents were not real. But then it seemed to me that the Thornburgh-Boccardi group did virtually no investigative work of its own to catalog the wide disparity of styles and typing techniques I found displayed in Texas National Guard memos. More recently, a private researcher who went to the Texas National Guard headquarters, as well as various archives and libraries across the U.S., has unearthed new documents. I have reviewed them and found that they include right-hand signature blocks, proportional spacing, odd abbreviations, a lack of letterheads, and other characteristics that were used to dismiss the Killian memos as being forgeries. [According to CBS News, "The Panel was not charged with investigating the authenticity of the documents." In e-mailed statements, CBS News drew attention to the panel's criticisms of Mapes, including its findings that "only the most cursory effort … was made to establish the chain of custody" of the documents and that "no one said that Mapes gave any indication of the level of controversy in her source's background."]

In the end, the panel prepared a document that read more like a prosecutorial brief than an independent investigation. And I think no one was happier to receive this condemnation of its employees than the executives at Viacom. Now they could present themselves to the Bush administration as victims of irresponsible, out-of-control journalists, not as an operation that was actually doing some tough reporting. Gosh, it had all been a terrible accident. [A Viacom spokesman says the panel and its findings "didn't have anything to do with Viacom. It happened at the CBS News level. Who are these executives and how does she know what they were thinking?"]

In early January, before the panel's damning report came out, Broadcasting & Cable magazine reported that CBS News president Andrew Heyward had met with White House communications director Dan Bartlett "in part to repair chilly relations with the Bush administration." According to the story, "Heyward was 'working overtime to convince Bartlett that neither CBS News nor Rather had a vendetta against the White House,' our source says, 'and from here on out would do everything it could to be fair and balanced.'" [According to CBS News, Heyward and Bartlett have met regularly over the years and "discussed a range of topics, as they always have, one of which was the National Guard story."]

I had to laugh at the use of the Fox News slogan by the magazine's source in describing the kind of coverage CBS supposedly promised the White House. Was that a slip of the tongue or a change in CBS's approach to coverage?

Mary Mapes, whose new book, Truth and Duty: The Press, the President, and the Privilege of Power (St. Martin's), is excerpted here, was a 15-year veteran of CBS News.

link to the original posting

1 comment:

it was very interesting to read. I want to quote your post in my blog. It can? And you et an account on Twitter?.

Post a Comment