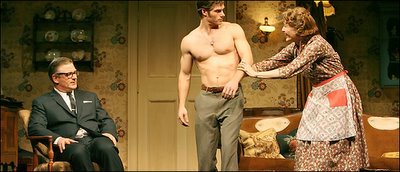

Note to the capture: Alec Baldwin, left, Chris Carmack and Jan Maxwell in "Entertaining Mr. Sloane." Sara Krulwich/The New York Times

February 26, 2006

THREE little words to make strong American theatergoers shudder: British sex farce.

Count me among those who can't hear a title like "Run for Your Wife" without wanting to run for the hills. It is all the stranger, then, to admit that I am looking forward — with something close to lust — to a show opening next month that technically falls within this loathed category. But let me put forward two other words that automatically nullify expectations of cozy titters and rib-nudging elbows: Joe Orton.

"Entertaining Mr. Sloane" — which opens on March 16 in a revival from the Roundabout Theater Company, directed by Scott Ellis and starring the auspiciously cast Alec Baldwin and Jan Maxwell — was the first full-length play and the first success in the brief, flaming career of Orton (1933-67). You could also say that it single-handedly dragged the British sex farce from the realm of seaside-postcard naughtiness into a land-mined field of subversion. In portraying two middle-aged, middle-class siblings drooling over the same cute young thing (a male hustler, in this case), Orton revealed not only the sagging flesh beneath his characters' rigorously conventional clothes but also the wayward, wanton itches beneath the skin. And how many other sex farces blithely factor in sadistic murder?

Sweet are the uses of perversity in the theater. Throw a kink, a curve, a warping twist into a time-honored dramatic formula and tried-and-true suddenly looks eye-poppingly new and unsettling. The spring season in New York is, happily and atypically, plump with demonstrations of such genre bending, with entrancingly wicked shows that extract the profane from the sacred and the rot from the pillars of society. If a majority of them turn out to be of British origin, that's because British artists have long used the perverse perspective as an essential corrective to their national class-conscious stolidity.

As it happens, the great Teutonic ancestor of the comedy of the perverse is on hand for inspection this season as well. That's "The Threepenny Opera," Bertolt Brecht and Kurt Weill's mordant 1928 reworking of John Gay's 18th-century "Beggar's Opera." Brecht's signature alienation effect was never writ as briskly or bouncily as it is in this capitalism-bashing study of thugs, whores and mercenary parents in Victorian London.

Bourgeois morality, and what have come to be called family values, are reflected and splintered in the cracked mirror of an underclass that eats its own for breakfast. Last revived on Broadway in 1989 (in a much-reviled production starring the rock star Sting), "The Threepenny Opera" is being reincarnated again, in a new translation by Wallace Shawn opening on April 20 at Studio 54, with a creative team that specializes in fashionable shock effects.

The director is Scott Elliott, a specialist in comedies of bad manners ("Hurlyburly," "Abigail's Party") and a man who believes that nothing suits the stage like an unexpected flash of full-frontal nudity (which he managed to inject even into Broadway revivals of "The Women" and "Present Laughter"). Alan Cumming, who won a Tony for playing that ultimate ringmaster of decadence, the M.C. in "Cabaret," shows up here as the polygamous archbrigand Macheath (a k a Mack the Knife).

He is sandwiched between two charmingly contrarian pop stars — Cyndi Lauper (the anti-Madonna of the mid-80's) as Jenny, the piratical prostitute, and Nellie McKay (the anti-Norah Jones of the mid-00's) as the demi-virginal Polly Peachum. The role of Polly's romantic rival, Lucy Brown — famously portrayed by Bea Arthur in the fabled Off Broadway revival half a century ago — is in this version played by a man, Brian Charles Rooney. Anything goes in the name of alienation.

Actually, the gangland violence of "Threepenny" is sure to seem demure next to the merry carnage of Martin McDonagh's "Lieutenant of Inishmore," directed by Wilson Milam and opening tomorrow at the Atlantic Theater Company. Mr. McDonagh, who explored the comic potential of bloodletting in rural Ireland in his dazzling "Leenane" and "Connemara" plays, here bravely applies his scalpel to the subject of Irish Republican terrorism. The play's none-too-bright hero is a torture-loving assassin whose mission is to make his country safe for cats. Warning: The show includes scenes of wholesale slaughter and dismemberment. Double warning: These scenes are criminally funny, or at least they were when I saw the show in London three years ago.

By contrast, Alan Bennett's "History Boys" is as sweet as figgy pudding, at least on the surface. A huge hit for the National Theater in London — which brings Nicholas Hytner's impeccably cast original production to the Broadhurst Theater for an April 23 opening — "The History Boys" follows the battle between two very different grammar school teachers for the hearts and minds of their students, who are preparing for Oxbridge entrance examinations. Think of it, perhaps, as an erudite cross between "Goodbye, Mr. Chips" and "The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie."

But as he has proved repeatedly in his earlier work ("Talking Heads," "Single Spies"), Mr. Bennett is expert in charting the deviant paths that curl within ostensibly ordinary lives. Both the dueling dons — juicily embodied by Stephen Campbell Moore and Richard Griffiths — have libidos that lead them into dangerous territory. The erotic dimension, though, is subjugated to the greater, and disturbingly pertinent, theme about how spin shapes what we think of as rock-hard history.

"History nowadays is not a matter of conviction," says one teacher. "It's a performance. It's entertainment. And if it isn't, make it so." And how does one do this, sir? "Flee the crowd. Follow Orwell. Be perverse."

to the original posting

No comments:

Post a Comment