April 19, 2006

Robert Farris Thompson

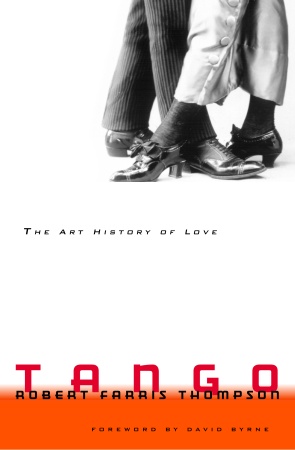

TANGO

An art history of love

368pp. Pantheon. £16.99 (US $28.50).

0 3754 0931 9

In London, the best way to hook up with a pretty Ukrainian, Japanese or Danish girl is to visit a salon such as Corrientes on a Saturday night. That’s hooking up in the sense of a gancho, a move in tango where the calf is hooked around the leg of your partner. Germans and Americans are dancing there too, plus a handful of black people – British, African and Caribbean. Your standard white Brits might constitute the largest single group, but they’re in a minority. Tango remains a dance to which immigrants are partial. Dance halls provide companionship if you’re new in a country, and tango offers a warmth of contact which makes one feel that one has friends – I have experienced this warmth of welcome myself when dancing in Cologne, Madrid and Paris, less so in Buenos Aires perhaps, but then there’s a difference – there you’re most definitely a tourist.

From the 1880s onward, the dance spots of Buenos Aires were frequented by single girls who arrived from the ghettos of Eastern Europe, and by men from Spain and Italy who came to work in the abattoirs and shoe factories that came into being owing to the wealth of good leather. Charities often disapproved of the single female immigrant in those days when emancipation was hardly taken for granted, and their censure led to the notion that all the salons of Buenos Aires were bordellos. This in turn, so the rumour goes, provoked the ire of the upper crust. The tango was seriously disapproved of in its native country; so much so that the adolescent Victoria Ocampo, who later founded the literary review Sur, was obliged to learn the tango in secret.

It is Robert Farris Thompson’s contention in Tango: An art history of love that the notion that tango had its provenance in the brothels is less a reason for its disesteem in the eyes of Argentina’s establishment than that its roots can be traced back to the Kongo Societies set up by the blacks of Argentina and prohibited to whites. Here, the grounded footwork of ceremonial African dance was fused with the embrace of European couple-dancing made familiar through the polka and the habanera. Thompson points out that the etymology of many of the terms associated with the tango, including the word itself, can be traced back to Ki-Kongo, a language of Central Africa. In creole Buenos Aires idiom tango means “A dance; a drum; a place of dance”. In Ki-Kongo tanga means “a festival”, tangala means “to walk heavily”. The names for related dances – candombe and canyengue – also have African origins. In addition, there is a Moorish influence via the influx of Spanish workers in touch with the floor-stamping zapateados of flamenco.

Never mind the fact that by 1887 the black population of Buenos Aires had been reduced to 2 per cent (the statistic is admitted by Thompson). In his view, the tango was very significantly formed by a black tradition which continues to haunt the dance. He makes some interesting observations: that African dancers made use of call and response – which may well have stimulated the evolution of the leading and following that epitomizes tango; that positioning oneself with feet apart and knees together is a sign of obeisance, like a curtsey, imported from Africa by the Kongo societies, and we may see a similar movement inserted into the swift and syncopated dance called milonga – a dance very close to the tango, enjoyed by tangueros along with the vals. He cites the stone faces and silence that ceremonial African dance entailed, and notes a similar absence of expression in the faces of tangueros, and he shows how among the Mande, Akan, Dahomea and Yoruba peoples the timing of the last gesture is critical, just as it is in the tango.

Thompson correctly identifies the arrastre – a sort of “vroom” that tango orquestas add to a significant note – as quintessential to tango, relating it to the grounded walk of the dancers. The strong, sliding push of their steps “makes visible the sweep of the sound”. This groundedness, indubitably an element of tango style, is a reinforcement, he maintains, of an element already present in the countrified dance music of the gauchos – many of whom were black. Thompson also refers to the now infamous report of Ventura Lynch, in 1883, that the tango, or more accurately the milonga, began when the, presumably, white compadritos – the tough guys – “burlesqued” the moves they had observed being performed by black dancers. He takes issue with this, insisting that not all such dancing was making fun of blacks, since some of the compadritos would themselves have been black, and “in the competitive spirit that was dominant in dancing . . . blacks would inevitably have excelled”. He goes on to list each and every dancer known to have African blood, every musician of colour, however few and far between they were in the predominantly Italian orquestas and ensembles of the 1930s and 40s, and he notes, interestingly, Dizzy Gillespie’s appearance with Osvaldo Fresedo’s tango band at the Rendez-Vous nightclub in 1956. He observes that certain figures are named after sweets and tells us that naming dances after sweets is black.

Some of this is already common knowledge. The Afro-Argentine pianist Rosendo Mendizábal is renowned for being the author of some of the first true tangos, and Facundo Posadas is a black tango star, known the world over, who is also a brilliant exponent of swing – fabulously kept alive and kicking by the B. A. Shimmy Club through much of the twentieth century. But black tango composers such as Mendizábal and more recently Horacio Salgán remain the exceptions to a Latin rule. As a dance favoured by immigrants, the grafts on to tango are more significant than its roots, though even in its origins it was a fusion. Criollo means “native” in Argentina, not creole in the sense of mixed race – but this is never admitted. While the author may be correct about its origin, tango might suggest a different etymology to a dancer of Italian extraction, perhaps related to the Latin for to touch, while in old Castilian tangir meant “to play an instrument”.

If you’re born of a black mother and a white father and you learn tango from sitting under your father’s piano, why is this an indication of black influence? Knocking the knees together may well be African, but we also find it in the czardas of Russia, and, as might be expected, in the charleston – but did the Buenos Aires manifestation of this come from the Congo or from Finnish sailors who had stopped off in New Orleans? Russian dances are also named after sweets – look no further than the dance of the sugarplum fairy; and most refined dance forms make a great deal out of the last gesture. Tangueros show stone faces and dance in silence, not because it is African in origin but because it is seriously difficult to do and they are concentrating! As to whose account is authentic, they are all difficult to prove, being largely oral histories backed up by a few journalistic snippets on etiolated newspaper. As Martha E. Savigliano points out in her anthropological study, Tango: The economy of passion, the dance’s history is prone to colonization by political expediency. In the 1930s, jaded Europeans thrilled to louche accounts of a dance born in the brothels of a country where men outnumbered women by fifty to one. As the dance craze threatened to define Argentina’s capital, the establishment there encouraged an origin in the “authentic” exoticism of the pampas, as nostalgically evoked by the singer Carlos Gardel. Tango history is “a garden of forking paths”, a labyrinth of stories.

In a chapter on film, Thompson fails to point out that the tango in Last Tango in Paris is competition ballroom tango, not tango Argentino at all, and at no point does he explain this crucial difference – one which television has also failed to grasp. He makes no mention of Naked Tango, Leonard Schrader’s brilliant evocation of Buenos Aires in the 1930s, starring, among others, Fernando Rey; presumably because its story of a judge’s wife, who changes places with a girl who has committed suicide aboard a liner, and ends up in a tango brothel, abets a history he rejects. In his chapter on music, he makes much of Horacio Salgán, who is indeed a great innovator, but fails to acknowledge band leaders of the calibre of Biagi. He pays scant attention to singers such as Edmundo Rivero, Raúl Berón or Alberto Castillo, and among contemporary ensembles picks out El Arranque, which is fair enough, but omits electronic groups such as Gotan Project and Bajo Fondo, both hugely influential. Worst of all, except for Eladia Blásquez, he misses out female singers – a line that starts with the cross-dressing Linda Thelma. Dorita Davis, Tania, Nelly Omar, Adriana Varela and Haydée Alba all go unacknowledged. Is it because they are white?

Thompson’s attempts at the description of dance steps are at best opaque. These he revels in naming – emphasizing that particular flourishes have been invented by black exponents. But his knowledge of the dance itself, emphasizing the faster, earlier variations – milonga, canyengue and candombe – seems limited to the views of a particular handful of ageing practitioners. Facundo Posadas, for instance, is oft-quoted, while important innovators such as Gustavo Naveira and Giselle Anne go unsung, as does Carlos Gavito and his partner. Naveira and Chicho Frumboli have moved the dance on from a collection of molecular figures with fancy names to an atomic notion of step-dynamics danced and taught from San Francisco to Istanbul by exponents of all races. This Tango Nuevo with its leanings-in and leanings-out – volcadas and colgadas – might have proved useful to Thompson’s argument, since he mentions cakewalk-like leanings in Congo dance. But the development of the dance since the now-dated days of the hit show Tango Argentino (1983) are nowhere dealt with, any more than is Miguel Zotto’s popular Tango por dos, or, perhaps more importantly, Mora Godoy’s brilliant dance drama Tanguera – either because the author does not know about it, or, as I suspect, because it again follows the porteño brothel theme which Thompson discounts.

I fear that Professor Thompson, the author of Black Gods and Kings, and African Art in Motion, has an onyx axe to grind. One senses that he is not interested in writing a comprehensive account of the tango – as the book’s cover proclaims – but only in tracing and emphatically asserting black influence on it, if not inserting such an influence into it.

As an overview of the tango, this is a bit of a one-note samba. If a comprehensive account of the phenomenon were possible, I would expect to learn as much about the polka as this author offers about M’tela funeral dances. I’ve heard that the vals was introduced in the salons to loosen the girls up for the close embrace demanded by milongueros. This may be a myth, but Thompson hardly refers to the vals at all. And the habanera? It gets a chapter to itself, emphasizing that it was danced by blacks in Havana, yet nowhere does the author say that it evolved from the French contredanse, whose origin was the English country dance. Tango takes on the colour of the immigrants who dance it: mazurkas, czardas and horas have all contributed hues. Thompson admits as much, but only just. However, when it comes to black roots, black innovation and black influence, he protests too much.

Why does “the issue of race” provoke such biased scholarship? Perhaps if this book had been titled “Black Contributions to the Tango” I would feel less oppressed by its bountiful euphoria (if not by its faux-gonzo style – cut to this, recall that). Exaggerated claims for African culture by Ivy League academics seem somehow condescending when the neglect of the Louisiana levees leads to homelessness, in the main for citizens of colour.

If you would like to read some excerpt from the book, please click here.

1 comment:

There ought to be a middle ground here. I set my alarm for 4:30 am.

Some days I don't make it out of bed, but most days I do and I enjoy getting my exercise in. I bought a light alarm clock and that has helped me a great deal. It's type of a balancing

act for me I tend to let my body rest around the mornings that I feel overly tired and sore.

My web site; list of muscles in the leg

Post a Comment