The New New York Times Building Project:

In development

Renzo Piano Building Workshop

Fox & Fowle Architects

New York Times Company New Headquarters

New York, NY

"Each architecture tells a story, and the story this new building proposes to tell is one of lightness and transparency."

-Renzo Piano

The Current New York Times Building and the pictures:

Panic on 43rd Street

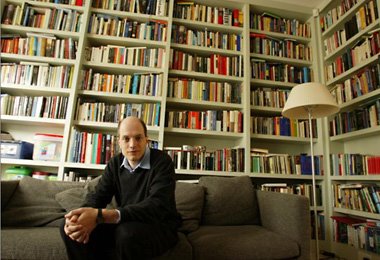

By MICHAEL WOLFF

By attacking The New York Times for reporting secret anti-terrorism measures, the White House has evoked the government-defying glory days of the “paper of record.” But even as the Times builds a soaring $850 million headquarters, its newsroom, its leadership, and its business are in a crisis of confidence

It's a different, much less awesome New York Times under attack for its decision to publish secret details of how banks are cooperating with the Bush administration to track terrorist finances. In the past, if you took on the Times, you took on its powerful eastern-establishment base; you took on the media itself. But the base this administration is most concerned with is always its own, and going after the Times—more a label for large parts of the country than a brand, a liberal caricature—seems to thrill it.

During the Bush years, the entire media has been so much easier to threaten because every company is under such relentless shareholder, financial, advertiser, and interest-group pressures—media organizations will do anything not to have politicians and prosecutors sniping at them, too. While the Times—historically, more like a branch of government than a mere commercial enterprise—has often operated as an exception to the rest of the media, it's hard to be a Cadillac in a fading American auto industry, and hard to be even the Times in the imploding newspaper business. The Times's current predicament—its share price has fallen by 50 percent since 2002; almost 30 percent of its shareholders protested the company's slate of directors at the annual meeting this spring—gets closer and closer to that of the Knight-Ridder papers, forced into a sale; the Tribune company, publisher of the Los Angeles Times and the Chicago Tribune, locked in a more or less mortal boardroom war; and Dow Jones, with its worried family members fretting about a sale of The Wall Street Journal. The Bush people cannot be unaware of this. In such a state of play, the Times is also doing that one thing that so often calls attention to a corporation's weaknesses and vulnerabilities and inflated sense of grandeur—a classic precursor to calamity. It's building a fabulous new corporate headquarters on Manhattan's West Side—a Renzo Piano–designed $850 million tribute to itself.

The calculation in the White House may well be that the Times is one of the few organizations that the weakened Bush people are strong enough to go after.

While the administration's anti-Times rants juice its base—made up of people who don't read the Times—the White House appears to be trying, with its drumbeat about treason and banking secrets, to stir up trouble with Times readers too (banking, unlike other hot-button conservative issues, is something that Times readers might get huffy about). The rub is that no one at the Times can be confident this cannot succeed.

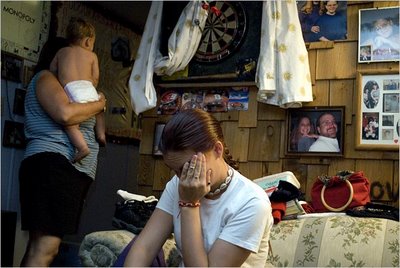

The familiar Times reader, the eastern-establishment reader—as dedicated and loyal and homogeneous an audience as few newspapers have ever had—has largely been abandoned by the Times. Or—a supposition the Times may share with the Bush administration—that audience simply may not exist anymore. Or it's just aged out of the economic mainstream. The new Times reader is … well, it's not exactly clear who the new reader is.

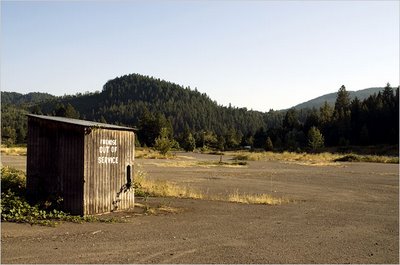

Unlike The Washington Post, which has put much of its editorial and business energies into dominating its local market, the Times's strategy—a doomsday scenario, foreseeing a one-newspaper nation, a last-man-standing paper—has been to make the paper national. Hence, The New York Times is no longer principally a metropolitan paper. With a daily circulation of 260,000 in the five boroughs, it's no longer even creditably a New York paper. (Its two tabloid competitors, the Daily News and the New York Post, have far more readers in New York City.) It's an Everyman suburban daily.

Here's the identity crisis: when the president is attacking it with all the media available to him, can the Times count on this new reader, and the advertisers who are courting him, not to doubt it? What beats in the heart of a reader of the St. Paul Pioneer Press whom the Times circulation-promotion campaign has persuaded to read the Times too? (In media-marketing terms, this new reader, the national urban-suburban yuppie type, overloaded on media choices—broadband, digital cable, satellite radio—is among the most fickle.)

Not only are the people at the Times aware of their new readers' likely lack of constancy, they're paranoid about it. In some sense, it's the central obsession at the Times, the driver of the place, this very un-Timesian concern with what people are thinking about it, as the paper increasingly becomes a hot topic in the national court of public opinion. And it's a crazy court. Every politically and emotionally addled information consumer wants to convict the Times of something.

Its two big scandals—the first about Jayson Blair, the reporter who made up an impressive catalogue of vivid stories, and the second involving Judy Miller, who, with the Times urging her on, went to jail for protecting her sources, whom the Times subsequently decided she should not have protected so much—were notable not just for the holes they revealed in the Times's journalistic operation but also for what they revealed about the Times's uncertainty about itself and its tendency to panic under pressure. Howell Raines, the Times executive editor whom the publisher, Arthur Sulzberger, appointed to turn the Times into a national paper—it was under Raines's watch that Blair wrote his fabricated stories—had the publisher's absolute support until the day he didn't and was fired. Judy Miller likewise had the publisher's absolute support until it was clear that P.R. considerations and the court of public opinion called for the opposite position.

The imperturbable Times has become ever so thin-skinned. Instead of a simple, traditional "We stand by our story" response to its critics over the banking revelations, the Times has offered a menu of defenses and rationalizations—on its editorial pages, in public letters, in interviews by editor and publisher. Its essential and contradictory defense—that it agrees some things should not be revealed because of national-security considerations, except when, in its own wisdom, it decides they should be—has not exactly helped. Its rather frantic need to explain itself to the Twin Cities reader—to stay in the good graces of both Middle America and an Internet of doubters—is too painfully obvious.

Karl Rove undoubtedly understood he could play on this desperation.

The Court of Arthur

And then there is the Arthur issue.

The Times, famously impersonal, suddenly has a flamboyant, hard-to-control, easy-to-dislike face. The right-wing editorialists at The Wall Street Journal, which also printed the story about the banking secrets, hurried to distance the Journal not so much from the story but from the Times, and particularly from the 54-year-old Sulzberger, by quoting gleefully from a self-aggrandizing commencement speech, delivered this spring at SUNY New Paltz, offering a vapid political message about the glories and disappointments of the 1960s and how they related to the Iraq war: "Sorry. It wasn't supposed to be this way."

The vulnerability that the Times critics see here—one that causes people inside the Times to gulp—is that difficult, less-than-humble, not-ready-for-prime-time descendants of 19th-century newspaper owners have been the cause of the decline and fall of a great many newspapers.

At the height of the Judy Miller business, just after he had fired her, after operatically standing behind her, Arthur appeared on The Charlie Rose Show. The most riveting thing about this appearance, more than his relative inarticulateness, was that there was no scenario under which it would be possible to imagine Arthur's father, Punch Sulzberger, the company's chief executive for more than 30 years and the steward of the modern paper, having done this—that is, publicly claiming to be the voice and the exemplar of the Times and its journalism.

The Times has prospered, and maintained its not-a-little loopy tradition of primogeniture, because the family, which holds voting power, has exercised it so lightly. If at all. The Sulzbergers—according to a former Times Company executive who was one of the designers of the Times management and shareholder structure—are supposed to be the British monarchy to the parliamentarians who actually run the show.

But there was Arthur on Charlie Rose—defending his company, his newsroom, his editorial decisions, his team. I remarked to this executive, an eminent and longtime Sulzberger adviser, on the oddity of a member of the Sulzberger family's actively managing the policies and editorial decision-making in the newsroom—in fact, representing the newsroom. My interlocutor drew back and said, "Editorial?… He's running the business side too! This wasn't supposed to happen!"

Arthur, on his own say-so, has accomplished a radical management restructuring of the company. He's consolidated, under his control, executive, shareholder, and editorial power—subverting the traditional autonomy of the Times newsroom. Indeed, executive editor Bill Keller is probably the weakest editor in the history of the paper. A company with a historically diffident management structure, where lines of power were always purposefully obtuse, now has a by-the-book, top-down org chart.

With such a figure—attention-seeking, immature, verbally feckless—at the center of the stage, it's hard to maintain a suspension of disbelief, let alone a straight face, about the rights of the firstborn. (This situation must have some resonance in the Bush White House.) The Times, with the scion insisting on his protean leadership, becomes, like any other corporation, judged by its top executive—it's not stronger than he is. Except, profoundly complicating matters, if he turns out to be weak, you can't easily replace this one.

It's Arthur himself who has most consistently articulated the fragility of the Times—its being-and-nothingness struggle in the changing media world. He seems so willing to embrace the sudden-death possibilities of the Information Age, so willing to disregard the conservative, wait-and-see approach favored by executives in Rust Belt–like businesses, that you wonder if there isn't, just a bit, a Munchausen-syndrome-by-proxy aspect to all of this. He gets to make the crisis; he gets to rescue the paper.

His strategy is to have the company face its core mortality—the inevitable end of a paper world—and then figure out what of its DNA can survive: Arthur is the baby Superman being jettisoned from planet Krypton. In modern management terms, the brand might theoretically be able to grow even if the physical product falls away. The newspaper might shrivel, but the Times can be a free-floating idea, somehow continuing in whatever guise offers itself and by whatever forms of delivery might be available—now or yet to be imagined (as they say in publishing contracts).

His vision of an ideal Times company sounds a lot like—without any sense of irony—Time Warner. (Once, during the boom years, I questioned Arthur about this enthusiasm for everything new-media. If this were the 50s, I asked, would he want the Times to buy a television network? "You bet I would," said Arthur.)

Seeing the Times as an acquisitive, multi-platform media company puts it, of course, in the same, ever compromised world of marketing and politicking as all other media companies. On the eve of the Iraq war—which it covered with a guilelessness that it has since apologized for—the Times, along with every other media giant, was petitioning the Bush F.C.C. to relax media-ownership rules to allow it to greatly add to its portfolio of television stations. (The Times's last annual report points to the television duopoly it owns in Oklahoma as one of its core achievements.)

Before scandal and a falling share price crimped their style, Sulzberger and Raines would talk openly about what they'd like to take over. They wanted the Financial Times or The Wall Street Journal and were looking for cable opportunities. (In 1993, the Times, in some misbegotten futurist idea that the Northeast was going to unite in a gigantic megalopolis, anchored by New York and Boston, bought The Boston Globe, which has performed poorly ever since.) When the chance arose, they snatched—for almost no logical reason, other than that they could—control of the International Herald Tribune (an enterprise with virtually no prospects of being anything more than a sentimental artifact) from The Washington Post, the Times's longtime partner in the paper. They did a convoluted deal with the Discovery network. They bought a piece of the Boston Red Sox.

But at the end of this deal-making spree, the most substantive and possibly transformative deal was the acquisition, for $410 million, of About.com. About.com? It's as unlikely an acquisition for the Times as any could be. About.com may actually establish the baseline for the lowest level of information available on the Web (which is saying a lot): a multi-million-page mishmash of superficial, often out-of-date, dumb, frequently wrong info bits, a place you never go by choice, but only because a search engine has been "optimized" (that is, tricked) to send you there.

Cyberia

The Internet is the great leap forward at the Times—with vastly more disruptive implications for the paper's future than the caviling of politicians.

For two generations, the Times business model has been to adeptly counter-program against more entertaining and technologically efficient ways to get news. It spent a lot (its news budget is among the largest of any news organization's) on deep and broad coverage, serving an elite, need-to-know audience, which, in turn, advertisers were keen on reaching.

Then, gamely, it gave in to the Internet. The premise is that, via the Internet, the Times can more easily deliver the Times. And, indeed, it's created the richest site of any newspaper in the world, a site whose depth and efficiency inevitably undermine the paper itself. At a conference earlier this year, hosted by Google, Arthur gave a talk about "real journalism," saying that the Times would succeed online because its brand had a proven record of probity—that people would always want the real thing. (His talk was accompanied by video clips of lots of older, exhausted-looking white men working in the newsroom.)

But more and more there is the sinking sensation at the Times that the Internet isn't Kansas. It's not just the relentless reductiveness of the new medium—the Times's long version becomes fodder for everybody else's short version. Or that the Internet requires, according to one hollow-eyed reporter, "everyone to do more and more for no more money." Much more unsettling than that: the Internet, once thought of as the ideal vehicle for reaching a targeted audience, is turning into a high-volume business, super-mass-media, dependent on cheap advertising. Success demands vast numbers: tens of millions or hundreds of millions of habituated users.

The Times, in newsprint form, with its daily 1.1 million circulation, and Sunday 1.7 million, makes between $1.5 and $1.7 billion a year (the company does not break out the exact figure). Times.com, with its 40 million unique online users a month, likely makes less than $200 million a year. Cruelly, an online user is worth much less—because his or her value can be so easily measured—than a traditional reader.

To replace its $1.5 to $1.7 billion traditional business with its online business—as it keeps suggesting it will one day do, and as critics have urged it to do on an even faster timetable—the Times might, impossibly, have to increase its online business to 400 or 500 million users a month. Or it will have to remake its content to more accurately reflect its advertisers' interests: oversize-shoe advertisers pay more to be next to a story about oversize shoes than they do to be next to a story about the Iraq war. Or, in another approach, it could look to MySpace: while the Times's 40 million monthly users generated, in May, according to ComScore, 489 million page views—this is the number that interests advertisers—MySpace's 50 million monthly users, deeply entertained by its user-created content, generated 29 billion page views.

The Times as we know it, as a pastiche of its paper self, can't succeed online (the whole idea that an old-time business can morph seamlessly into a huge, speculative entrepreneurial enterprise is a kind of quackery). At best, it might become a specialized Internet player, having to drastically cut its current, $300 million news budget. What it might providentially become, however, is About.com, a low-end, high-volume information producer, warehousing vast amounts of advertiser-targeted data, harnessing the amateurs and hobbyists and fetishists willing to produce for a pittance any amount of schlock to feed the page-view numbers—and already supplying 30 million of the Times's 40 million unique users.

They'd get red in the face disputing this at the Times. They'd say new business models may develop online, possibly paid models, or the price of advertising may increase, or something—because people will always want the Times, won't they? On the other hand, these same managers bought About.com. They know the future is equivocal.

Taking StockAnd then there are the shareholders—much scarier than the Bush people. The owners of the Class B stock—the Sulzberger-Ochs family, who hold voting control—are, in a very real sense, supported by the A shareholders, who own most of the company. It's the A shareholders who maintain the price of the stock. It's the B shareholders—50 or so descendants and spouses—whose daily lives are supported by the dividends produced by the stock.

The traditional assumption is that, for media companies, the market understands and accepts two tiers of stock (Murdoch's News Corp. has two tiers; The Washington Post has two tiers; Viacom has two tiers). If you don't like it, you don't buy it in the first place. But in this new age of shareholder activism, two tiers suddenly become a juicy wedge issue.

The activist shareholders are—not dissimilar to the Bush White House—waging a press campaign against the Times. The dissidents—only Morgan Stanley Asset Management, with 5 percent, has taken a public stand, but Bruce Sherman's Private Capital Management, which forced Knight-Ridder into a sale, is one of the Times's largest shareholders—are claiming that the B shareholders, presiding over scandal, are being reckless with the Times's brand and with their stewardship of a national treasure. (To cut costs and raise revenues, management is trimming the width of the paper by 1.5 inches, reducing news coverage by 5 percent, and selling ads on the front page of the Business section.)

They're characterizing the B shareholders as, in effect, being in it for themselves, pointing to Arthur's ever increasing multi-million-dollar compensation package—$3.2 million in 2005.

They are also using the "governance" word. By challenging the "governance" of a company—the independence and responsibility of its board—you question its integrity and uprightness (i.e., its fundamental Timesness). And, truly, the Times board—controlled by its B shareholders—is a passive and lackluster bunch. Whereas Warren Buffett is on the Washington Post board, the Times board's one corporate star, IBM's former C.E.O. Lou Gerstner, resigned in frustration several years ago.

In any conventional sense, control of the company, as long as the family stays united, is invulnerable. And most people take the fact of that unity as a historic given. But now it's being tested in the face of shareholders whose activism effectively talks down the price of the stock, the point on which management, the board, and the family are most accountable, and does it with the one other thing the Sulzbergers are perhaps most touchy about—bad press.

What will the B shareholders give to make it stop?

The fear in the newsroom is that the first thing to be given up will be bodies—fire enough people and earnings improve and stock creeps up and that takes immediate pressure off management. (It's already begun: "There's no money here," hissed a reporter to me recently in what had been a little gossip about expense accounts.)

But if that's not enough—and it never is enough—then what's next is more independent board members, followed by little changes in the nature of control, and then asset sales, and lots of secret meetings among family members on the subject of what to do about Arthur, and then a plan afoot to take the title of publisher from him, and on and on … until … the powers that be face the dreadful discrepancy between the declining fortunes of business as usual and a more probable upside of dismantling, selling, and letting the market have its certain way.

The form for projecting and maintaining great authority is, most classically, to talk softly. But that's not a modern media idea. The modern idea is to fight it out in the marketplace. All media is big media, rising and falling. Operatic. Building corporate as well as architectural monuments to itself. The Bush administration, as much a media enterprise as a governing one, has gone into the media marketplace to try to upend the Times, which it sees as one of its brand and message competitors—one that it can efficiently take on. This seems to me another Bush miscalculation. Its invective is actually brand enhancement for the Times, recalling the Times's real journalism, and evoking an era before the Times cast its fate with all the players and all the visions and all the clashes of the titans in the great media soup, or, worse, before—despite all its efforts to be something else and to forestall the inevitable—it got caught out as just another newspaper company coming to its natural end.

For a dwindling number of us—over-50 Manhattanites, over-50 Jews, over-50 liberal-minded people, over-50 journalists—that's a "God is dead" sort of statement. It's too big. Too existential. And, anyway, how do you exactly define "end"? You mean NO New York Times? Nada? Darkness?

Well, yes, in effect.

Michael Wolff, a Vanity Fair

contributing editor, is the author of Autumn of the Moguls

(HarperBusiness) and Burn Rate: How I Survived the Gold Rush Years on the Internet

(Simon & Schuster).