Karen Kephart, a former lumber mill worker in Oakridge, Ore., had the kind of good-paying job that has all but vanished from the town of 4,000.(Leah Nash for The New York Times)

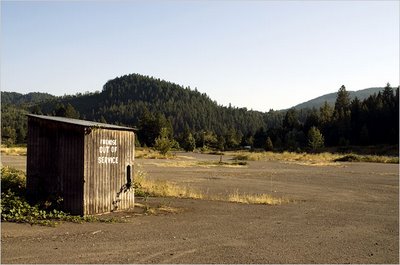

On the west slope of the Cascades, Oakridge is an hour from Eugene. A shack is all that remains at a former lumber mill site.(Leah Nash for The New York Times)

Dazzle Deal lives in a trailer park with Dillinger, 5, and Viviana, 3. To make ends meet, she sometimes cleans motel rooms and braids hair.(Leah Nash for The New York Times)

On the edge of town, where the old Pope and Talbot mill burned down in 1991, an industrial park was created, but it is covered largely with weeds.(Leah Nash for The New York Times)

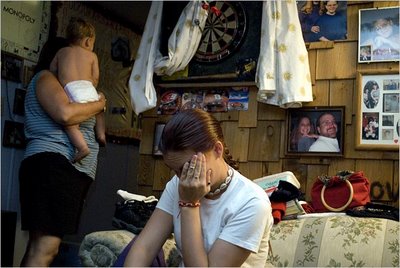

Kaydee Huffman, 22, gets ready to work the graveyard shift at the Village Inn Restaurant. She makes Oregon’s $7.50 minimum wage, and tips. She lives with her mother, Tami Parrish, 44; her son, Derrick Cologna, 1, who receives medical care under a federal medical program for poor infants; and Ms. Parrish's husband, an unemployed cook.(Leah Nash for The New York Times)

Above the fog line and below the snow line, with herds of elk in the surrounding hills, Oakridge offers a peaceful beauty, and residents say it is a perfect place to live, except for the lack of jobs.(Leah Nash for The New York Times)

Wade Miller, 47, left, and George Marlow, 51, are unemployed and live in trailers in Mr. Miller’s mother’s yard.(Leah Nash for The New York Times)

When jobs dried up, many of the more enterprising families left Oakridge.(Leah Nash for The New York Times)

“This is the hardest thing I’ve ever done,” said Shella Hylton, with her daughter Genesis, 1. The transient family lives in a camper in the forest.(Leah Nash for The New York Times)

by Erik Echholm

OAKRIDGE, Ore. — For a few decades, this little town on the western slope of the Cascades hopped with blue-collar prosperity, its residents cutting fat Douglas fir trees and processing them at two local mills.

Into the 1980’s, people joked that poverty meant you didn’t have an RV or a boat. A high school degree was not necessary to earn a living through logging or mill work, with wages roughly equal to $20 or $30 an hour in today’s terms.

But by 1990 the last mill had closed, a result of shifting markets and a dwindling supply of logs because of depletion and tighter environmental rules. Oakridge was wrenched through the rural version of deindustrialization, sending its population of 4,000 reeling in ways that are still playing out.

Residents now live with lowered expectations, and a share of them have felt the sharp pinch of rural poverty. The town is an acute example of a national trend, the widening gap in pay between workers in urban areas and those in rural locales, where much of any job growth has been in low-end retailing and services.

Most parents here, said Shelley Miller, who heads the family resource center at the public schools, are “juggling paycheck to paycheck.”

Ms. Miller included herself. She makes $20,000 a year, and when she and her 16-year-old daughter make the hourlong drive to Eugene, she said, “It’s a treat.” They go to Subway for dinner, then to Wal-Mart to shop at far lower prices than they could at Oakridge’s single supermarket.

Expressed in 2005 dollars, the average pay for a full-time worker in rural Oregon fell to $27,600 in 2005 from $34,200 in 1976. Over the same period, average pay in urban counties in Oregon climbed to $37,800, putting the rural-urban gap at $10,200 and rising, according to the Oregon Employment Department.

About 700 Oakridge residents, from a population of about 4,500 in Oakridge and the surrounding area, visit a charity food pantry each month to pick up boxes of groceries worth $100 apiece. Two-thirds of public school students qualify for free or reduced-price lunches, meaning their families are near the poverty line or below it. About 260 of the town’s 1,200 housing units are single-width trailers.

“Every fall we discover that a few families have lost it over the summer and are camping out in the woods,” Ms. Miller said. “So we help them find some kind of housing in town.”

Above the fog line and below the snow line, with herds of elk in the surrounding hills, the town offers a peaceful beauty, and residents say it is a perfect place to live, except for the lack of jobs.

Today, a latte-serving cafe caters to mountain bikers and travelers on their way to a ski slope or parts farther west. A few new fast-food outlets are interspersed with graying motels and empty storefronts. Former workers fondly recall how the town’s 10 bars were mobbed every payday; now, a few old-timers gather in one of three tired bars and a dingy Moose Lodge, needing little prompting to carp about the Forest Service and environmentalists.

Oakridge has struggled to find a new economic base. On the edge of town, where the old Pope and Talbot mill burned down in 1991, an industrial park was created, but it is covered largely with weeds.

The town has authorized water and sewer services for up to 200 prime home sites in the hills above, and it hopes to attract retirees and commuters from the Eugene area, said Don Hampton, a City Council member.

Along with a growing trade in outdoor recreation, becoming a distant bedroom and retirement community may be the town’s best hope, bringing tax revenue and service jobs, though it is not clear how much opportunity this will offer ambitious young people.

“There’s no substitute for having a payroll,” said Dan Rehwalt, 77, who worked for decades as a machinist with lumber mills and the railroad.

When the logging and mill jobs dried up, many of the more enterprising families left. Some fathers commuted for nine months at a time to log in Alaska. Others found jobs an hour or two away in Eugene and other towns, but almost always at lower wages.

Karen Kephart, 63, who has five great-grandchildren, was one of the first women to work alongside men at the giant Pope and Talbot mill. When she was laid off in 1989, she was running a saw for $13 an hour, equal to $21 in 2005 dollars. Her husband tried other mill work in the region, then retired. To make ends meet, Mrs. Kephart turned to caring for the elderly in Eugene, sometimes for $7 an hour.

“We had to use our savings to live on,” Mrs. Kephart said in the trailer park that she and her husband moved into after selling their house on the hill, and where they get by on Social Security and modest pensions. “It changed our retirement considerably.”

Their daughter Tami Parrish, 44, the second oldest of five children, remembers having “to scrimp and save everything we had” after the mills closed.

Ms. Parrish and her two sisters live in the same trailer park as their parents. She too has worked as a caregiver in Eugene, in a home for Alzheimer’s patients. She grossed $1,900 a month, but she recently had surgery for carpal tunnel syndrome and is not working.

Crowding into her trailer are her husband, an unemployed cook; her 22-year-old daughter, who just started a waitress job making Oregon’s $7.50 minimum wage, and tips; and the daughter’s baby boy, who receives medical care under a federal medical program for poor infants.

The two Kephart sons have fared better: one, after leaving the mills, was hired as a railroad conductor, rose to engineer and lives “uptown” in Oakridge with his wife and five children. The other works in a fiberglass plant in North Carolina and helps out with money sometimes, Mrs. Kephart said.

Dazzle Deal, 26, with tattooed arms and a pink pony tail, has three children, ages 7, 5 and 3. She is part of a more recent influx of poor people who moved to Oakridge because it seemed a safe place to raise kids on little money.

Ms. Deal moved from Las Vegas four years ago, paying $3,000 for a dilapidated trailer in the park where the Kepharts live and fixing it up as best she could.

For nine months she worked at a charity in Eugene, hitchhiking 55 miles each way because she had no car. Then the charity closed. More recently, she has occasionally found work cleaning motel rooms and braiding hair.

“If I worked at McDonald’s or Dairy Queen, it would almost cost me more to pay someone to care for the kids,” she said. She gets $400 worth of food stamps and is on Medicaid; her main challenge is coming up with $205 each month for lot rental in the trailer park.

A swing set outside her trailer attracts other children from the trailer park, and on a recent warm day she took a group of them to wade in the nearby river.

One family, the Hyltons, live in an RV in the forest and describe themselves as transients, after returning to Oregon from a spell in the Southeast. But it is not clear how and when they might move on.

Robert Hylton, 42, was living hand to mouth on a river bank with his wife, Shella, 30, and their daughters, ages 1 and 2. Strain showed on the face of Mrs. Hylton as she washed clothes in a tub.

The family catches trout to eat three times a week. Mr. Hylton drives, or bikes when there is no gas money, into Oakridge for food baskets and the occasional construction job.

“We’re trying,” he said, “to figure out what to do next.”

No comments:

Post a Comment